"The Case for Unpopular Clients" [Jonah Goldberg]

I'm really surprised that the opposing view the Journal picked to match up against Andy's op-ed was so weak. It's not weak because it's bad, per se. It's just irrelevant to most of the issues. Stephen Jones argues that lawyers should be willing to take on unpopular criminal defendants as clients. Okay, nobody I know disagrees with that, and he makes an entirely adequate case for it.

But that's not what the debate is about. The debate is about, among other things: Whether DOJ should be able to hide the history of appointed lawyers from Congress and the public; Whether Gitmo detainees are criminal defendants at all; whether volunteering pro bono for declared enemy combatants is even analogous to working for other "unpopular clients" or whether that pro bono work was really an effort to use the legal system as a Trojan Horse to change national security policy. And on these and other fronts, Stephen Jones' argument is just deficient or non-responsive.

For starters, most of his essay is dedicated to the hardships he endured representing Tim McVeigh. Just going from his version of events, I'm entirely sympathetic to his case. He didn't deserve any of that. But what does any of it have to do with what we're talking about? He was a "draftee" into the case, by his own admission. That alone makes his experience different. Throw in the fact McVeigh was an American citizen, not a member of a foreign terror organization, and that his whole piece is almost entirely a response to an argument no one is making, and one has to wonder why the Journal even bothered running this piece. It would have been a lot more edifying if they found someone to actually respond to Andy's far more substantial argument.

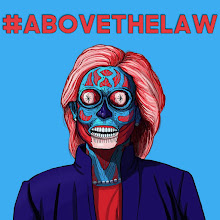

That said, there is one point where Jones scores a glancing blow. If you watch the Keep America Safe ad there is the insinuation — or at least reasonable people can infer it — that KAS is suggesting the "al Qaeda 7" are pro-al Qaeda. If that's the insinuation some are trying to make, I think that's counter-productive. I don't think these lawyers are traitorous or anything like that (which is not to say that it's impossible). I think they subscribe to a coherent ideological view about the war on terror and priesthood of the lawyer class. I think that view is dangerous, wrong and naive, but it ain't treason.

Is the Gitmo Bar Pro-Islamist? [Andy McCarthy]

I appreciate Jonah's kind words. In fairness to Stephen Jones, I didn't know about his essay and I don't know whether he was told I'd be writing one. It wasn't pitched to me by the Journal as a point/counterpoint thing. They asked me to write about the issue from my perspective, and the only guidance I got was a suggestion that I address some precedents if any seemed relevant. (I thought Eric Holder's Heller brief was highly relevant — particularly, the fact that no one came close to suggesting that the position he staked out on the Second Amendment as a private lawyer was off-limits in considering what he might do as a top policy-making official.) I imagine they did the same thing with Mr. Jones. By contrast, when I did a point/counterpoint thing for USA Today earlier this week, I was told in broad outline what themes their editorial would hit (I wasn't shown the actual editorial) so I had a better idea what I needed to respond to.

Now, to the more important question posed in the last paragraph of Jonah's post. Let's put DOJ's ten (and counting) Gitmo lawyers to the side and just talk about the volunteer Gitmo bar in general. I believe many of the attorneys who volunteered their services to al Qaeda were, in fact, pro-Qaeda or, at the very least, pro-Islamist. Not all of them, but many of them. The assistance many of them provided went disturbingly beyond any conventional notion of "legal representation." (And let's not forget that what Lynne Stewart called her "legal representation" of the Blind Sheikh was later found by a jury to be material support to terrorism.) I expect we'll be hearing much more about this in the coming days.

Islamism is a much broader and more mainstream (in Islam) ideology than suggested by the surprisingly ill-informed comments Charles Krauthammer made about a week ago (see Dr. K's commentary here; Mark Steyn's reaction, with which I agree, is here.) Jihadist terrorists are a subset of the Islamists, but many Islamists disagree with the terrorists' means — they are mostly on the same page as far as ends are concerned.

Personally, I don't think there is much difference, if any, between Islam and Islamism. In that assessment, I'm not much different from Turkey's Islamist prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who claims it is "very ugly" for Westerners to draw these distinctions between Muslims as "moderate" or "Islamist" — “It is offensive and an insult to our religion," he says, because "there is no moderate or immoderate Islam. Islam is Islam, and that’s it."

Islamists are Muslims who would like to see sharia (Islamic law) installed. That is the necessary precondition to Islamicizing a society. It is the purpose of jihad. The terrorists are willing to force sharia's installation by violent jihad; other Islamists have varying views about the usefulness of violence, but they also want sharia, and their jihadist methods include tactics other than violence. I reluctantly use the term "Islamist" rather than "Islam" because I believe there are hundreds of millions of Muslims (somewhere between a third to a half of the world's 1.4 billion Muslims) who do not want to live under sharia, and who want religion to be a private matter, separated from public life. It is baffling to me why these people are Muslims since, as I understand Islam, (a) sharia is a basic element, and (b) Islam rejects the separation of mosque and state. But I'm not a Muslim, so that is not for me to say. I think we have to encourage the non-sharia Muslims and give them space to try to reform their religion, so I believe it's worth labeling the sharia seekers "Islamists" in order to sort them out. But I admit being very conflicted about it because I also concede that the Islamists have the more coherent (and scary) construction of Islam. We wouldn't be encouraging reform if we really thought Islam was fine as is.

In any event, Islamist ideology is multi-faceted. You can be pro-Islamist, and even pro-Qaeda, without signing on to the savage Qaeda methods. And the relevant question with respect to progressive lawyers is not so much whether they are pro-Qaeda as it is whether, as between Islamists and the U.S. as it exists, they have more sympathy for the Islamists. That's a fair question, but a very uncomfortable one to ask. Indeed, as Jonah broaches it, he softens it to whether the insinuation that the lawyers are pro-Qaeda is "counter-productive." That's an interesting question but a very different one from whether the insinuation is true.

In a column a few days ago, I addressed the insinuation this way:

“Al-Qaeda Seven” reminds me of another legal shorthand expression: “mob lawyer.” It’s a common expression — everyone uses it. I’d wager that a number of the DOJ’s Gitmo lawyers have either used it or been in conversations where it rolled effortlessly, and without objection, off the tongues of other prosecutors. “Mob lawyers” are lawyers who regularly represent members and associates of the mafia. It’s such a commonplace that even the mob lawyers call themselves “mob lawyers.” It’s a handle; it doesn’t mean the people who use the term don’t see the moral difference between mobsters who commit heinous crimes and the lawyers who defend them. Same with the “al-Qaeda Seven.”

Much of the commentary on this point, including from some people who usually know better, has been specious. The normally sensible Paul Mirengoff, for example, huffs, “It is entirely inappropriate to suggest that these lawyers share the values of terrorists or to dub the seven DOJ lawyers ‘The al-Qaeda Seven.’” The values of the terrorists? Which values?

Jihadists believe it is proper to massacre innocent people in order to compel the installation of sharia as a pathway to Islamicizing society. No one for a moment believes, or has suggested, that al-Qaeda’s American lawyers share that view. But jihadist terrorists, and Islamist ideology in general, also hold that the United States is the root of all evil in the world, that it is the beating heart of capitalist exploitation of society’s have-nots, and that it needs fundamental, transformative change.

This, as I argue in a book to be published this spring, is why Islam and the Left collaborate so seamlessly. They don’t agree on all the ends and means. In fact, Islamists don’t agree among themselves about means. But before they can impose their utopias, Islamists and the Left have a common enemy they need to take down: the American constitutional tradition of a society based on individual liberty, in which government is our servant, not our master. It is perfectly obvious that many progressive lawyers are drawn to the jihadist cause because of common views about the need to condemn American policies and radically alter the United States.

That doesn’t make any lawyer unfit to serve. It does, however, show us the fault line in the defining debate of our lifetime, the debate about what type of society we shall have. And that political context makes everyone’s record fair game. If lawyers choose to volunteer their services to the enemy in wartime, they are on the wrong side of that fault line, and no one should feel reluctant to say so.

No comments:

Post a Comment